Synchronization Recap

Take a quick glance here to refresh your concepts.

Some key concepts from the Comet Book (yeah the one that killed the Dinosaurs, ha):

- A critical section is a piece of code that accesses a shared resource, usually a variable or data structure.

- A race condition arises if multiple threads of execution enter the critical section at roughly the same time; both attempt to update the shared data structure, leading to a surprising (and perhaps undesirable) outcome.

- An indeterminate program consists of one or more race conditions; the output of the program varies from run to run, depending on which threads ran when. The outcome is thus not deterministic, something we usually expect from computer systems.

- To avoid these problems, threads should use some kind of mutual exclusion primitives; doing so guarantees that only a single thread ever enters a critical section, thus avoiding races, and resulting in deterministic program outputs.

Requirements

Remember that a solution to the critical-section problem must CHECK all these requirements:

- Mutual exclusion. This property guarantees that if one thread is executing within the critical section, the others will be prevented from doing so.

- Progress. If no process is in its critical section and some want to enter, the decision is made only by processes that are actively competing for entry, not those doing other tasks. This ensures that selection happens without indefinite delay.

- Bounded waiting. A process that requests entry to its critical section will get in after a limited number of other processes have entered.

Solutions

Peterson's Solution

Is discussed here.

Hardware Instructions

To ensure safe access to shared resources, we use atomic operations, meaning they execute without interruption. This improves performance and prevents race conditions.

However, implementing atomic execution for all instructions would require special hardware. Instead, we generalize the concept using specific atomic operations, such as:

test_and_set();compare_and_swap().

This allows synchronization without requiring entirely new machine architectures.

Commented code to each of them can be found here.

test_and_set() is commonly used for implementing simple locks. It atomically tests if a lock is already set and then sets it, ensuring only one thread can acquire the lock at a time.

compare_and_swap() is used in lock-free data structures because it compares a memory location with an expected value and swaps it if they match. This allows for atomic updates of pointers in structures like lock-free stacks, queues, and linked lists.

Lock-Free Example: compare_and_swap() enables concurrent push and pop without a mutex, as seen in lock-free stacks. Since it avoids traditional locks, it is less susceptible to deadlocks and helps in high-performance, multi-threaded applications.

In the Dino Book (Figure 6.9, page 268) we are told compare_and_swap() does not meet the bounded-waiting requirement. However, we receive a solution for that:

// elements in waiting are initialized to false

// lock is 0

// a process Pi can enter when waiting[i] == false

// OR

// key == 0

// Pi POV

while(true) { // while I want to enter the CS

/* ENTRY SECTION */

// 1. Declare interest in entering the CS

waiting[i] = true; // Pi is now waiting

// 2. Let's acquire the lock

// the 'key' variable determines if the lock was

// successfully acquired

key = 1; // 1 means the lock is closed

// loop loop loop until

// a) waiting[i] = false (we've been granted access from some other process)

// b) key becomes 0 aka lock is free

while (waiting[i] && key == 1)

// We attempt to set the lock from 0 to 1 atomically

// lock is 0 (free) => key becomes 0 so the loop exits

// lock is 1 (occupied) => key remains 1 so the loop continues

key = compare_and_swap(&lock, 0, 1);

// I no longer want to wait, I proceed into the CS

waiting[i] = false;

/* CRITICAL SECTION */

/* EXIT SECTION */

// I must allow another waiting process (if it exists) to guarantee fairness. So we're scanning the array in a cyclic order.

// The next process following Pi

j = (i+1) % n;

// Keep scanning until we find a waiting process, otherwise loop back to Pi

while ((j != i) && !waiting[j])

j = (j+1) % n; // just the next process

if (j == i)

// We found no other process waiting

// So we'll release lock

lock = 0;

else

// We found a process waiting

// We "hand over" the permission, by deactivating waiting and allowing Pj to exit its busy-wait loop and enter the CS

waiting[j] = false;

/* REMAINDER SECTION */

}

Liveness

Liveness refers to a set of properties that a system must satisfy to ensure that processes make progress during their execution life cycle. A process waiting indefinitely under the circumstances just described is an example of a “liveness failure".

A very simple example of a liveness failure is an infinite loop. A busy wait loop presents the possibility of a liveness failure, especially if a process may loop an arbitrarily long period of time.

Deadlock

Deadlock is covered here.

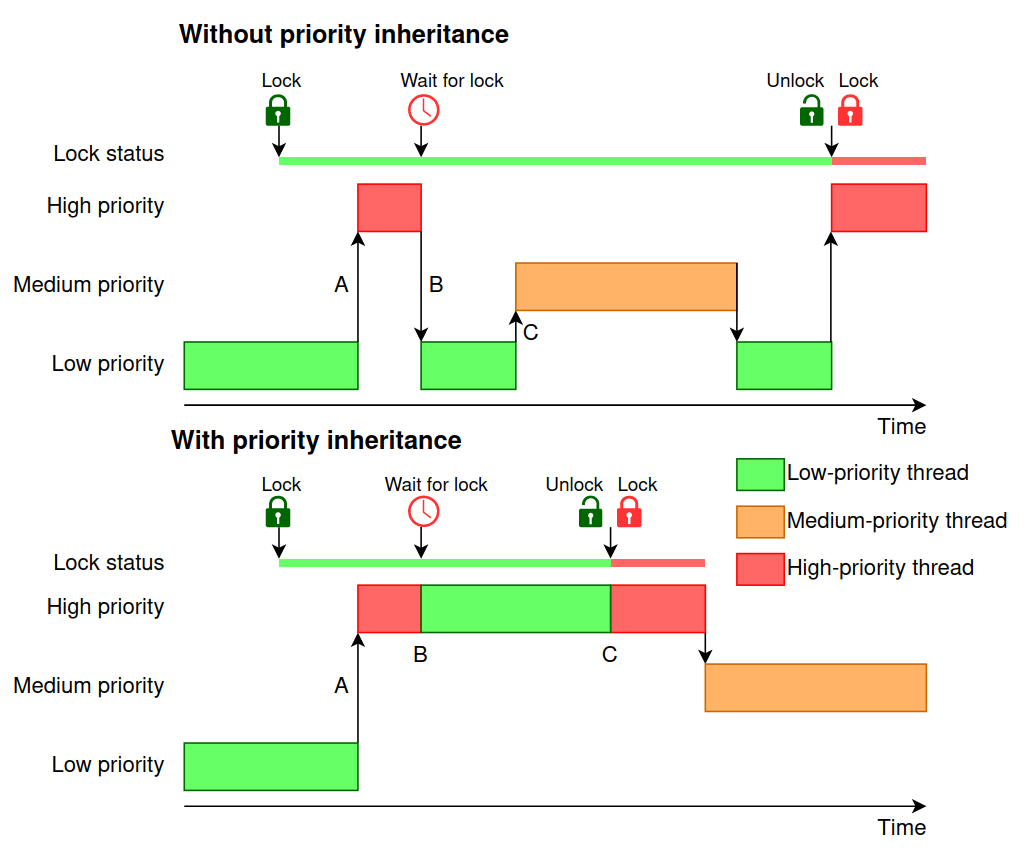

Priority Inversion

Further Reading

- What really happened on Mars Rover Pathfinder

- Real-Time Programming: Priority Inversion

- Monitors - Neso Academy

References

- Operating Systems Concepts, 10th edition, Chapter 6 - Synchronization Tools

- Operating Systems - Three Easy Pieces, Part II - Concurrency